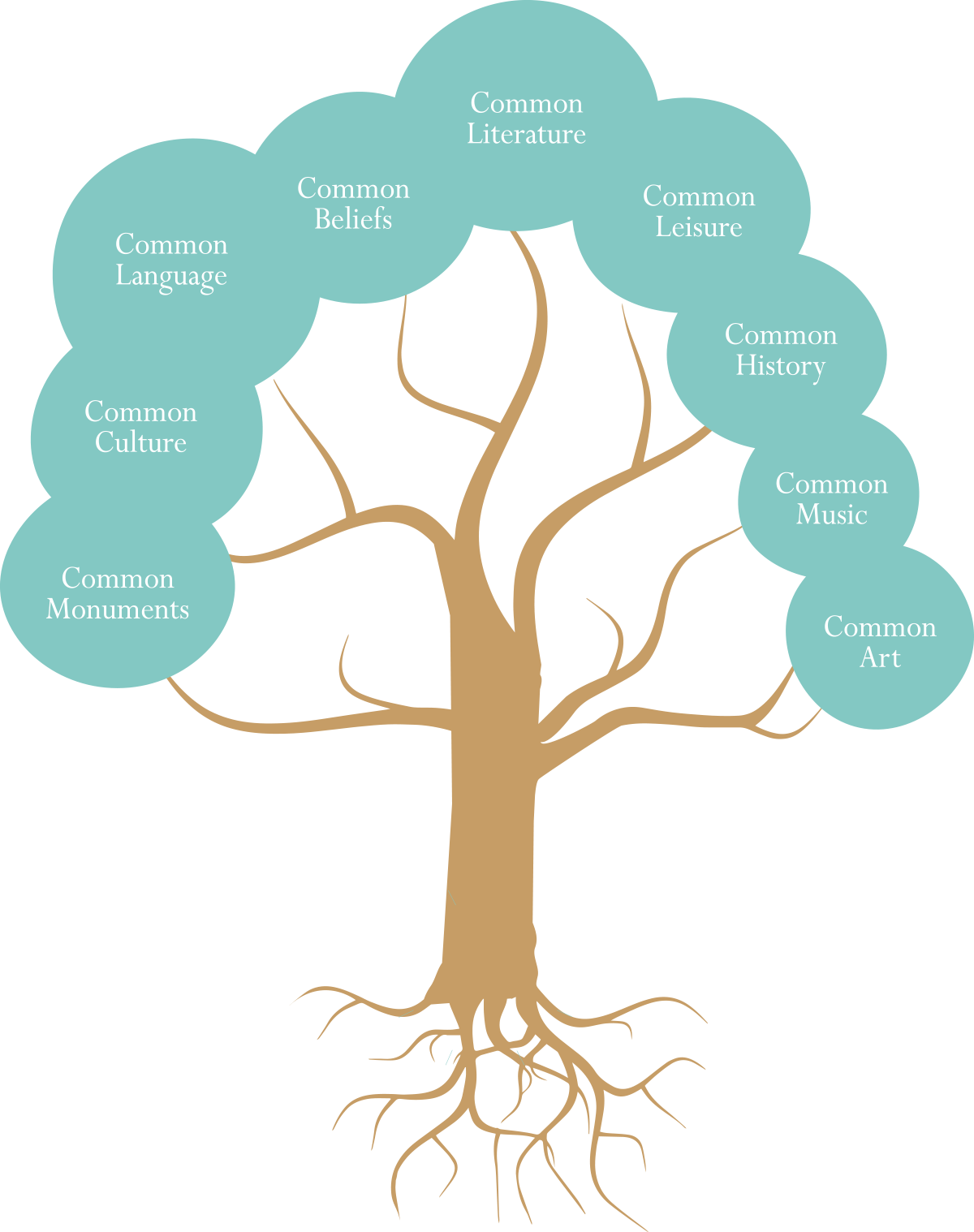

Common Identity Tree - click on each circle of the tree for information.

A narrative that promotes the Common Identity of these islands beginning with the word Pretani. The Pretani are the most ancient inhabitants of the British Isles to whom a definite name can be given.

Common Monuments

The ancient monuments found across the British Isles such as Newgrange, Stonehenge, Skara Brae and Callanish were built by the Pretani. Such visible reminders of our islands’ ancient inhabitants — the dolmens, stone circles and other burial monuments — are still treated with great respect.

Tampering with these monuments can even today, according to some, bring bad luck upon the perpetrators, and archaeologists have been refused permission to excavate some monuments because of local resistance.

At the beginning of the century W.G. Wood-Martin wrote: “Facts which show the resentment formerly felt by the country people at their disturbance, are well known. It is noteworthy that these former objects of the peasants’ veneration were erected by an early wave of population. It may be suggested that their preservation by means of veneration for traditional beliefs points to the continued influence, up to a very late date, of their builders.”

Common Culture

The Pretani are the most ancient inhabitants of the British Isles to whom a definite name can be given.

Pretania or the Isles of Pretani is the first known name of the islands now known as the British Isles.

While initially hunter-gatherers the Pretani would develop farming within the islands.

The Pretani were a matriarchial society and had a matrilinear form of inheritance.

The great Phoenician ships of Tarshish, according to Aristotle, discovered the island of Ierne (now known as Ireland), “beyond the Celts”, which in their language means “the uttermost habitation”.

As trading increased between the islands and other nations, the Pretani society grew to become one in which craftsmen were in greater numbers than warriors. The Pretani lived in a time of peace allowing the development of skills such as mining, ship-building, metallurgy, pottery and jewellery to develop.

This golden era would not last, as a result of the arrival of Julius Caesar in Gaul in 58 - 51 BC. Caesar’s arrival with his army would create the greatest effect on the Pretani as they pushed European tribes across to the islands, soon to be followed by the Romans. The lasting legacy would be a change to the name of the islands and the people, the establishment of a patriarchial society and wars.

Julius Caesar changed the name of the islands Pretannia or the Isles of Pretani to Britannia .The ‘P’ in Pretania was changed by Julius Caesar under the influence of the Gauls to a ‘B’, thus creating the word Britannia for the southern area of the largest island. The word Britannia would eventually be used to describe all the islands and in English they are known as the British Isles.

Gaul

Gaul was an ancient region of Europe, corresponding to modern France, Belgium, the south Netherlands, SW Germany, and northern Italy. The area south of the Alps was conquered in 222 BC by the Romans, who called it Cisalpine Gaul. The area north of the Alps, known as Transalpine Gaul, was taken by Julius Caesar between 58 and 51 BC.

Common Language

Remnants of the Pretani language remain in modern times, such as the name Islay. Islay refers to the island that lies off the west coast of Scotland and 25 miles off the north of Ireland.

There are place-names in many parts of Great Britain, especially river names (which are well known to preserve remnants of older languages), which are Pretanic in origin.

- English examples are the river Ouse, and the Thames-Teme-Tamar-Teviot series

- Northern Scotland examples are the rivers Isla, Affric, Liver, Nevis and many others.

Some Pretani tribal names are Caledonia, Taezali, Vagomagi and Venicones of historical Pictland (known today as Scotland), the latter tribe becoming the Venniconii of modern Donegal.

An early Pretani kingdom in Ireland was Robogdium and a later Pretani or Cruthin kingdom in Ireland was Dalaradia.

This language of the Pretani would be changed, as other languages such as Brittonic and Gaelic entered the British Isles, creating a linguistic hotch-potch in modern Scotland, which we know today as Pictish. This is reflected in the Bressay inscriptions.

As language changed within the islands, the word Pretani would become Cruthin in Ireland. And the word Pretani would become Prydain in Britain. The word Prydain is still used today and is found in the British passport.

Common Beliefs

Whatever beliefs the Pretani held — what we now call the Elder Faiths — have obviously long disappeared, yet perhaps it is possible to detect faint echoes of them in long-established rural superstitions and folk memories, such as not damaging or removing a Fairy Thorn.

Estyn Evans wrote that archaeology was now tending to “confirm what recent anthropological, linguistic and ethnographic research suggests, that the roots of regional personality in north-western Europe are to be found in the cultural experience of pioneer farmers and stockmen, quickened by the absorption of Mesolithic fisherfolk… One should probably look to the primary Neolithic/megalithic culture rather than to the intervening Bronze Age as the main source of the Elder Faiths.”

Common Literature

Any literature by the Pretani has not survived. However, there is widespread literature which contains remnants of the Pretani stories captured in Brittonic, Gaelic, English and Scotch scripts.

Among the great works of early Irish literature are a group of tales known as the Ulster Cycle. These were written in the Pretanian Abbot Comgall’s monastery of Bangor and are traditionally felt to depict the north of Ireland in the first few centuries AD and speak of the Cruthin (Pretani). While some scholars suggest that certain of the episodes enshrined within these tales have some bearing on actual historical events, this can only be speculation. But perhaps what we are looking at here is the hidden history of the Pretani.

What we can say, however, is that the whole structure of society as depicted in the sagas, the weapons and characteristics of the warriors, and their methods of warfare, agree precisely with the descriptions by classical authors of life among the Brittonic speaking people before the Roman invasions. So, while we cannot yet take them as ‘historical’ evidence, these stories nevertheless give us a glimpse, albeit romanticised, into the islands’ Iron Age — its ‘Heroic’ Age — and are, moreover, a rich ingredient of this island’s cultural heritage.

Common Leisure

With the development of farming by the Pretani in the islands now known as the British Isles leisure time was created. People no longer had to use all their time to find food allowing ‘free’ time to develop civilization.

Popular games would have often been vestiges of warfare, practiced as a form of sport.

Musical instruments were likely created for ritual purpose. Pottery, painting, drawings and other early art forms provided a record of both daily life and cultural mythology. Beads and other types of jewellery were created as external symbols of individual status and group affiliations.

When an activity was no longer useful in its original form (such as archery and horse-riding for hunting or warfare), it became a form of sport, offering individuals and groups the opportunity to prove physical skill and strategy. Often, the origin was a religious ritual, in which games or drama were played to symbolize the continuing human struggle between conscience and the lack of it.

Common History

The first known name of the British Isles, the Isles of Pretani and the name of the people, the Pretani are well documented.

The Greeks have a history of settlement in the area of land now known as France. They established a colony in Massalia, known today as Marseille in the South of France. Massalia became one of the major trading ports and was at its height in 400 BC. The most famous citizen of Massalia was the mathematician, astronomer and navigator Pytheas.

Between 300 and 330 BC the Greek geographer and voyager Pytheas, organized an expedition by ship into the Atlantic, taking him past the islands as far as Iceland, Shetland and Norway, where he was the first scientist to describe drift ice and the midnight sun. In his “Concerning the Ocean”, he gave the earliest reference to these islands, calling them the Isles of Pretani, (Pretanikai nesoi,) a name the people used themselves, the meaning of which will never be known.

These names had come to the general knowledge of Greek Geographers such as Eratosthenes by the middle of the third century BC. Together they were known to the Greek speaking warriors, via their allies the Celtic speaking warriors, as the Pretanic Islands or Islands of the Pretani.

Between 60 – 30 BC Diodorus Siculus, a Sicilian, who was a Greek historian and geographer wrote Bibliotheca Historica. Within this book he has recorded the name the Isles of Pretani. Around 50 BC Diodorus wrote about “ those of the Pretani who inhabit the country called Iris (Ireland)

Common Music

The Pretani would have had ancient forms of music such as the Dunmanway Horn (found in west Cork) and the Wicklow Pipes.

The Pretani music is the oldest, deepest music that exists in Europe and America, carried eventually from the western highland fringe of Europe by that most ancient of peoples, the Pretani, to the Appalachian mountains.

It is a Serpentine trail, one made by the mountains themselves, as that vein of green mineral can be found from Georgia to Nova Scotia and on through Ireland, Scotland, Wales and Cornwall to the very Orkneys themselves. So are we made by the mountains, and our music also, from the Gaelic singing of Stornoway to the Caledonian soul, from the choral psalmody of Bangor and St Gallen to the Hill songs of Tennessee.

Common Art

Ancient Pretani art is captured in the symbols of ancient monuments such as Newgrange and the northern monuments in Scotland.

The Pretani Logo captures this symbolism.

And it isn’t just for their religious impact that the later Christian monks of Pretania are renowned, but for the manner in which they inscribed and illuminated their magnificent manuscripts. Drawing upon the traditional art of their pagan past, Pretani monks decorated their great manuscript books and the accoutrements of their churches with designs that are a breathtaking reminder of the art of the Pretani. Margins overflow with patterns of swirling, interlocking lines, and entire pages are given over to scriptural pictures that are a kaleidoscope of colour and restless patterns.

Perhaps the most famous of these Bible pages are the dazzling ‘carpet pages’, covered in their entirety with patterns that rival the delicacy of the finest metalwork and the brilliance of enamel or precious stones. Some of these manuscripts, notably the Book of Kells, the Book of Durrow, and the Lindisfarne Gospels, are considered to be among the world’s greatest art treasures